Don’t put AI in the Driver’s Seat of a Human Centred Design Project

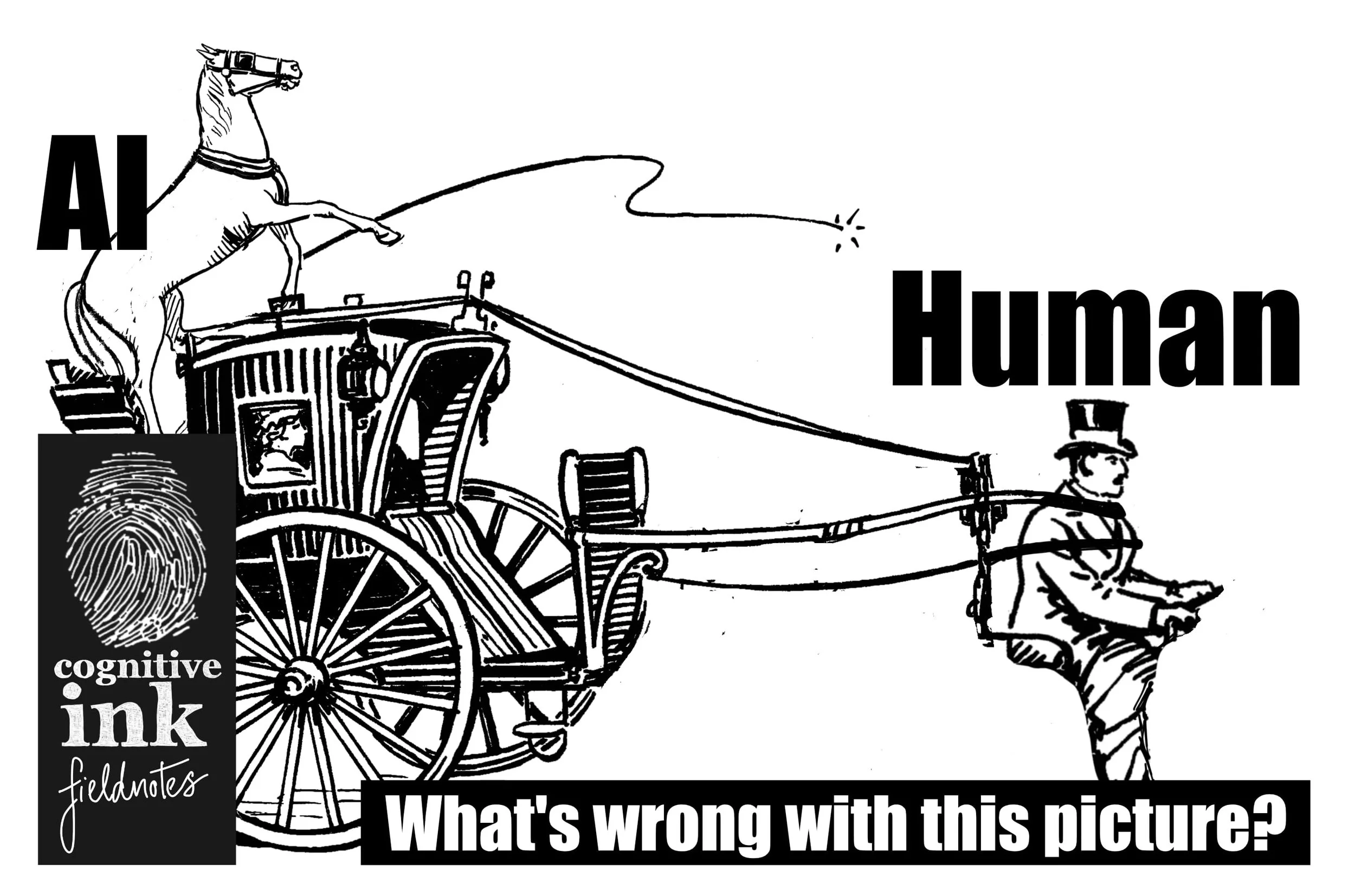

If AI is the horse, the thing meant to do the work, then they should pull the cart, to wherever the driver specifies, not the other way around.

Imagine you’re suddenly transported to Victorian England, circa the late 1800s. Like the fog-shrouded metropolis evoked (and fictionalised) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories. There’s be things you’d expect: noise, period-dress, moustaches and things that might surprise you, the smell of burning coal and the mud.

But how stunned would you be if you saw, when hailing one of the famous hansom cabs, to find a horse driving the carriage? That’s what we want to avoid when exploring any new tool, but especially with the Generative AI / Large Language Model / AI tools that appear to offer such extensive capability.

If AI represents a new, and still somewhat unknown and unpredictable capability, then it’s important to make sure that we, the drivers, drive the horse, not the other way around.

We should put human needs at the centre of our thinking and solve outwards to find the right technologies, which might, or might not be AI.

Put another way, stripped the story of its amusing Victorian trappings; we should start by understanding what problems we want to use AI to solve, and then investigate whether AI has the capability, safety, suitability, reliability, and more.

That’s how Human Centred Design works. It puts human needs at the centre of a solution and solves outwards to find the right technology capabilities to address those needs. That might be what we’re all calling ‘AI’, or it might be something older, more well-understood and more reliable.

If AI is going to be part of a solution-set, you can borrow a handy checklist from Christopher’s thinking at Adventures in a Designed World and his “Principles of Human-Centred AI Design”. This includes a series of key questions:

What problem are we solving?

What are potential benefits and harms?

Will people be pushed upward or pulled downward by use?

Have we considered bias?

Who’s being exploited?

Have we carried out small-scale tests (and what have we learned)?

Experiment with AI, but use caution and keep experiments survivable

Granted, we can and should still experiment with new tools and technological capabilities. That is a viable path to discovering either new human needs, or new ways to solve existing problems.

But that experimentation, especially with AI, should be framed and managed in a controlled, separate setting, not in a production environment or living workspace.

Taking another nugget of gold in Christopher’s “Adventures in a Designed World”, risky technological experiments can be managed with Peter Palchinsky’s (an influential Russian engineer from the 1900s) and his ‘Rules of Practical Failure’.

Seek out ideas and try new things.

When trying something new, do it on a scale where failure is survivable.

Seek out feedback and learn from your mistakes as you go along.

Number 2, “Try new things at a scale where failure is survivable” is especially pertinent here. It might not be a survivable mistake to roll out AI organisation-wide, to employees, or, give it straight to customers and users, before you understand what it can, or can’t do.

AI isn’t a perfect fix for every issue. It’s a complex technology, with a number of surprising usage implications.

In the future, you might end up using AI as a capability, so experimenting with its capabilities makes sense. But do so in a safe environment, and with an awareness of the ethical, cost, and environmental impact.

The way to thrive with this sort of technology on the horizon is to understand the human, system and organisational problems and solve outward to the technology.

That way we can build the sort of future where organisations and the people they serve, both benefit.

References

Original Public Domain Horse and Cart Image from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hansom_(PSF).png